Principle 2: Data Privacy

Respect Peoples’ Private Domains

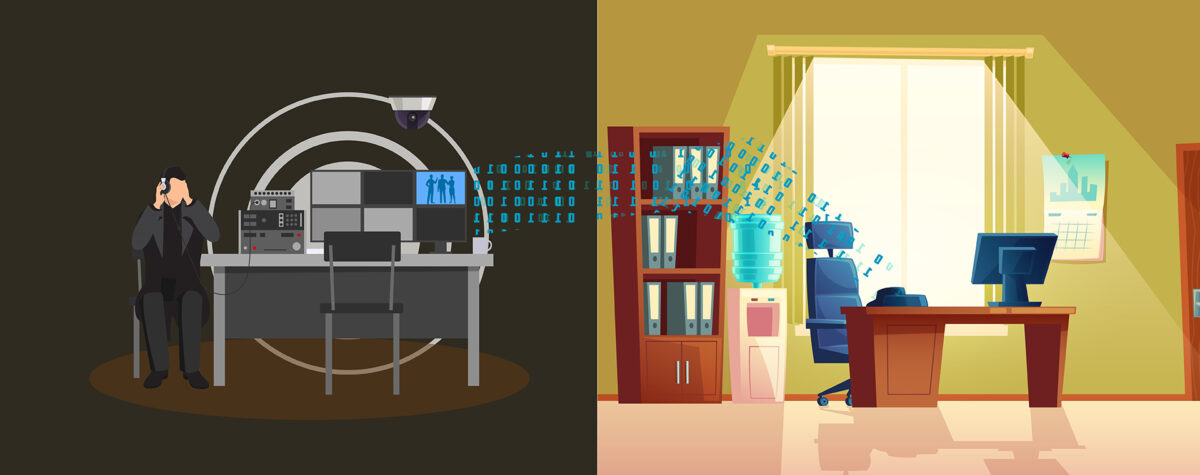

When states and companies collect data about you, they come to know a lot about you. Do they violate your right to privacy? And what does that even mean?

At Seluxit, we believe that people own data about themselves (See The Principle of Data Ownership), but we also believe that people have a right to privacy over certain private domains. So what is the difference between the right to data ownership and the right to privacy? In this article, we will try to answer that question, and explain why we believe in the Privacy Principle.

An Important Distinction

First, it is crucial to make the following distinction, when talking about privacy: There is a distinction between the condition of privacy and the right to privacy. When companies or states collect data about Smith, his condition of privacy changes. That is to say, he loses privacy to some degree.

However, that does not necessarily mean that the companies or states have violated Smith’s right to privacy. If Smith gave informed consent beforehand, his privacy right has not been violated. But his condition of privacy has still changed, since his privacy has been diminished. The Privacy Principle is only concerned with the right to privacy.

The Right to Privacy

What does it mean to say that Smith has a right to privacy? It means, among other things, that he should be able to control whether Jones has access to data about him. But it also means that Smith has the right to control access to certain private ‘domains’ of his, even when no data about Smith is located within this domain. Such domains can both be digital, like a database, or physical like a house. Let’s look at two examples:

Example #1

Imagine that Jones is a very good hacker. Without Smith’s permission, Jones gains access to Smith’s Google Drive. On the drive, Smith only stores – with his grandmother’s consent – a copy of the data from her SmartMeter, in order to see if her daily routines change. A change in routines can be a sign of developing dementia. Jones´s intention was to find unflattering pictures of Smith on the drive, in order to blackmail him.

According to the Privacy Principle, Jones has violated Smith’s right to privacy, and arguably also the grandmother´s (the grandmother owns the data), even though Smith does not own the drive, nor the data stored on it. This shows that Smith has certain privacy rights over certain domains, even if he does not own the domain, nor the data located in it. Therefore, the Principle of Data Ownership is not enough. We also need the Privacy Principle.

Example #2

Let us consider another example. Jones wiretaps Smith’s phone, in order to learn compromising facts about Smith, which he will use to blackmail Smith. As it happens, Smith does not use his phone during the time in which Jones is wiretapping it.

According to the Privacy Principle, Jones has violated Smith’s right to privacy, even though Jones does not obtain any data about Smith. Again, this shows that the Principle of Data Ownership is not enough. We also need the Privacy Principle.

The point of these examples is simple: It is possible to violate someone’s right to privacy, even if no data has been accessed.

An Objection

Having read the examples above, one might raise the following objection: The Privacy Principle is in fact not necessary, as long as the Principle of Data Ownership applies. That is, we can explain Jones’ wrongdoing in the examples above (and any other case normally described in terms of privacy) as attempts of violating Smith’s property rights over his data: Jones is wrongfully trying to get access to information about Smith without Smith’s consent, but fails.

Our reply to this objection is the following: Imagine that in example #1, Jones’ intention was to gain access to the grandmother’s data, not Smith’s. He might not even know that it was Smith’s drive, he was hacking. In that case, Jones would not have attempted to gain access to data about Smith, and yet Jones clearly seems to have violated Smith’s right to privacy.

Compliance with the Privacy Principle

When Seluxit collects and processes data, we respect both the Data Ownership Principle and the Privacy Principle: We only collect or process the data, which users have given us access to voluntarily and we do not collect data in users’ private domains without their consent. All data is anonymized so that no individual user is identifiable, and users´ private domains are respected.

You have a right to privacy over data about you, but you also have a right to control access to your private domains.